Reviews (886)

Violent Night (2022)

In the golden age of Hong Kong cinema, when several dozen action films vied for viewers’ attention every year, the rule was that the way to distinguish one’s film from those of the competition was to include previously unseen attractions, or at least a unique screenplay, setting and overall visual or subgenre stylization. The filmmakers from 87North Productions consciously follow the Hong Kong tradition in many respects. Unfortunately, however, over the four years since they stopped being mere subcontractors providing choreography for action scenes and started producing movies themselves, they have reached a point where, instead of amazement and excitement, their films evoke only a superficially altered impression of something that has already been seen. This was inevitable, because unlike in the case of the major productions from the golden age of Hong Kong cinema, they have nowhere to grow. On the one hand, they have no competition, but no one will entrust them with bigger budgets that would enable them to further develop. Furthermore, they don’t have any stars other than Keanu Reeves who would devote themselves to the action genre, work on themselves and continually impress viewers with new stunts. On the other hand, it didn’t matter that Nobody is a variation on John Wick, because the film was carried by the excellent Bob Odenkirk. The same was true of Kate in relation to Atomic Blonde thanks to Mary Elizabeth Winstead and the pop-Japanese stylisation. Not to mention that in both of these cases the choreography worked with real physical aspects and a specific setting. But Violent Night not only comes across in its choreography as a derivative of the same company’s previous films, but the thing that is supposed to make it different is in itself derivative. The whole film blatantly paraphrases Home Alone and Die Hard, this time with Santa Claus himself battling the highly capable bad guys. Unfortunately, in practice this is all reduced to the insipid juvenile attraction of Santa cursing with a broken nose and a blood-soaked beard through most of the film. Of course, he also uses Christmas items like tree ornaments to eliminate his enemies. However, the film peculiarly comes most alive when it dispenses with the would-be shocking of American viewers stupefied by the illusion of Christmas and moves to the attic in the manner of Home Alone and to the tool shed in the style of Commando. But even these flashes of inventiveness (though still derivative) cannot obscure the desperate fact that David Harbour doesn’t have the charisma to carry an entire film on his own and that Tommy Wirkola is a master of gimmick movies whose final execution falls far short of the promise of their catchy concepts.

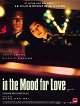

In the Mood for Love (2000)

Wong Kar Wai’s intoxicating puzzle comprising moments of excruciatingly chaste love and quiet longing is composed of glances, gestures, still lifes, colours and delicately chosen borrowed music. All of the cinematic means of expression are used here to create and sustain an atmosphere in which the heightened emotionality of hidden love is combined with plaintive melancholy and veiled in dreamy nostalgia. Tony Leung’s sad eyes and Maggie Cheung’s graceful silhouette in a collection of exquisite cheongsams with expressive patterns become the emblems of this fragile work. In fact, it’s almost paradoxical that In the Mood for Love deals with the fleetingness of moments when Wong is capable of imprinting them so incredibly intensely on film, even though that is due to tremendous work in the cutting room following his creative method, where he lets the actors, who are absolutely immersed in their characters, develop only vaguely outlined situations through improvisation. From this flow of time captured on a pile of material, he subsequently seeks out the moments in which the slightest change in facial expression mirrors an inner emotional storm. What’s rather surprising is the unexpectedly funny, though still emotionally stirring motif of the games that the two platonic lovers play with each other. Because of their concerns about the emotional impact of foreseen situations, they practice their reactions, only to succumb completely to their hidden feelings at the given moment of the test. ____ In addition to the depiction of a relationship and a masterful ode to love, In the Mood for Love is also a metaphor for Hong Kong as a lively space and a crucible of relationships, identities and political contexts. Wong intentionally leaves the contrast of intimate space and external history aside for most of the time, instead composing most of the film from cut-outs of the characters’ immediate personal environments. In nostalgic retro vignettes, he also highlights the solidarity and togetherness of people based on more than just the shared spaces of rented rooms in the apartments of families with grown-up children. The sudden intrusion of major history at the end of the film, even in the form of something as banal and peaceful as an official state visit, is thus all the more incongruous and radical. Wong thus carefully points out the historical context that he subtly hints at earlier in the dialogue, when the supporting characters mention their plans to leave Hong Kong because of the tense situation there. The film is set in the period of the left-wing demonstrations of the 1960s, but at the time when it was being made, it resonated with the exodus of Hong Kong residents due to Britain’s handover of the colony to China. The impact of such an exodus and severing of ties is depicted in the tragic passing of the central characters in the last part of the narrative. The final segments with the temple spaces, whose walls are imprinted with the life stories, desires and emotions of the people, but which are completely devoid of life, seem to foreshadow a vision of a dehumanised Hong Kong stripped of its identity, which is formed by its residents, such as those whose yearning we have been observing throughout the film. Today, when Hong Kong filmmakers have to resort to self-censorship due to China’s enforcement of the national security act, In the Mood for Love can be an instructive example of how to work with hints and hidden meanings while preserving the essentially local atmosphere of films. On the other hand, the bitter fact that Wong’s subsequent films lack both the authenticity and emotional urgency of his work shaped by the genius loci of Hong Kong at the end of the 20th century perhaps best attests to the merciless fleetingness and inimitability of that era, when Hong Kong was still able to search for and explore its identity before it was forced to fight for it, suffer for it and then silently remember it.

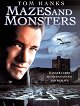

Mazes and Monsters (1982) (TV movie)

For a time, Mazes and Monsters was renowned as a mythical relic. But let’s acknowledge that its renown was based exclusively on exaggerated external factors and contexts. It seems tremendously enticing in that Hollywood’s most beloved star, Tom Hanks, had his first role in a TV movie that demonised Dungeons & Dragons, which was allegedly a component of the “Satanic panic” or rather the fear of conservative societies that fantasy would foster Satan worship among the nation’s youth. In the new millennium, this legend grew thanks to the internet as a dumping ground for useless trivia, which was fundamentally influenced by the fact that it was not easy to get access to the film, as it was released only on VHS. After watching Mazes and Monsters, however, the whole bubble bursts completely and the most that one can take away from it is the knowledge that Tom Hanks has always run with his hands held strangely away from his body like Forrest Gump – in other words, the legend is just another completely useless and disproportionately exaggerated curiosity, just as the film itself is. Mazes and Monsters remains a mediocre television melodrama about an unstable young man for whom playing a game becomes a trigger for his personal psychological problems, but in which there is no demonisation of role-playing games. It’s possible that the film’s creation was motivated by the producers’ attempt to ride the moral panic of the time. However, if that was actually the case, then the most surprising thing is that they didn’t in any way exploit or thematise it. We hopefully sense exploitation tendencies at the beginning, as all of the players in the film’s paraphrase of D&D come from wealthy families in which traditional maternal roles have broken down in various ways. However, this foreshadowing remains only a pipe dream of the diggers of film trash. In fact, the rest of the film doesn’t offer any witch hunts or even any significant conflicts. We simply spend 100 minutes watching the uninteresting characters of four college kids who play role-playing games finding out that one of them has a problem, and the others trying to help him in a confusing but ultimately relatively successful way. With the renewed interest in D&D thanks to the popularity of Stranger Things, the legend of Mazes and Monsters rose from the ashes, which eventually led to the film’s release through VoD and an enthusiast Blu-ray edition. As is the case with most such legends, however, this will only lead to the revelation that the allegedly magnificent Holy Grail is nothing more than an ordinary trinket wrapped up in a fantastic story worthy of a proper game master.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

“Don't dream it, be it.” Done. Several times already and perhaps many more to come.

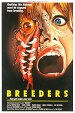

Breeders (1986)

Trash purveyor Tim Kincaid cooks up his own bizarre paraphrase of slasher flicks in which serial-killer murders are replaced with insemination by an alien monster. The absence of any filmmaking talent, from a feel for pacing to guiding of the actors, doesn’t prevent Kincaid from apparently taking his deliriously muddled miscarriage seriously. Thanks to that, he subjects viewers to moralising pronouncements from the mouths of the wooden actors and lets them bitterly experience everything, including those monologues. However, he also knows very well that his overwrought exploitation of the dangers of the night-time streets of New York in the 1980s needs proper attractions for the viewer. Therefore, the film abounds with shots of nudity, which comes across like an absurd promenade in see-through swimsuits thanks to the preference for sunbathing in bikinis. All of this is topped off with the closing sequence, in which the blank expressions of the actors prove that the counter-shots were filmed separately and the actors had no idea how or to what they were supposed to react. One would like to say that Breeders radiates Ed Woodian naïveté, but that’s not the case, as it only enviously gazes at that from a thicket of artless imbecility, which, together with the incoherent premise, may diminish the extent to which it is unintentionally funny.

Please Don't Eat My Mother! (1973)

Please Don't Eat My Mother! is one of the more playful works in the category of voyeuristic nudies. However, that doesn’t mean that it offers any sharp entertainment. In the interest of shooting as quickly and cheaply as possible, this rip-off of Corman’s The Little Shop of Horrors and Meyer’s The Immoral Mr. Teas goes the route of the longest possible shots with the most drawn-out monologues, during which the amateurish actors are allowed to needlessly blather on. In the end, the prevailing impression of the whole film crystallises as artlessness bordering on impudence in the sense of how close to the edge of the soft- and hardcore categories the filmmakers could allow themselves to go, as well as how they didn’t bother with any spatial causality of the sequences during the actual voyeurism. But perhaps one shouldn’t think too much about how the protagonist sitting in a crouching position can see inside a car where someone is making out.

Army of Darkness (1992)

Army of Darkness should have been many things, especially in the eyes of fans of the preceding films of the Evil Dead franchise, but also partly from the perspective of the filmmakers, which is reflected in, among other things, the existence of four different versions of the film. In the end, the version released to cinemas remains the best, as it condenses the essence of the film and of Raimi’s style. The result is the most comic-bookish film not based on a comic book and the best animated movie in a live-action format. Raimi makes Ash a dime-a-dozen hero along the lines of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, or rather Tommy Monaghan or even Jérôme Moucherot, who keeps finding himself in all kinds of goofy adventures in various genre settings. In addition to that, he gives his previously completely unexplored hero an appropriately absurd background, or even an origin story. But he also endows him with a distinct personality for the first time in a parody of tough-guy comic-book heroes, thus making him not only ultra-macho, but peculiarly also a ridiculous simpleton, asshole and buffoon. Contingent on a contractual commitment to the studio, Raimi conceived this sequel to the Evil Dead franchise as a pure provocation in which he unrestrainedly piles up frantic fantasy premises and joyfully plays around with special effects. Thanks to the fantasy framework, he was able to paraphrase and elaborate on his favourite special-effects sequences from Gulliver's Travels and Jason and the Argonauts in his own style. On top of that, he had at his disposal both an adequate budget to execute a range of delightfully handmade and honestly primitive tricks, and mainly the living visual effect that is Bruce Campbell. Army of Darkness definitively established Campbell’s persona as an actor, which many of his later roles would paraphrase (and which is fundamentally different from his actual nature). We could even say that this stylised Campbell is the film’s main character, as indicated by “Bruce Campbell vs. Army of Darkness” in the opening credits. Raimi self-indulgently counters the character traits described above by making the actor the live-action equivalent of animated slapstick characters. In Evil Dead II, he let Campbell’s slapstick acting shine spectacularly, for the purpose of he again creates entirely gratuitous but enchantingly entertaining sequences interspersed with other visual effects. Raimi works with Campbell as he would with an animated figure that he can deform in all possible ways, multiply and, mainly, expose to bizarrely painful but, at the same time, non-injurious hardships. We can also find parallels with the expressive means of animation rather than live-action film in other formalistic aspects of Army of Darkness. Raimi thus variously combines action with live actors and stop-motion animation and finds ingenious ways to handle the shots of the army of the dead by combining the background with actors in costume with puppet animation in the foreground. Of the myriad imaginatively shot sequences with toy-like qualities, I’ll highlight the fight with the witch, where Raimi uses various techniques to enhance the impression of fast and wild action. In addition to slow motion and leaving out frames, we can find here another method used exclusively by animators of slapstick films, who do not draw anatomically accurate phases of movement in individual frames, but instead deliberately draw them in a deformed or exaggerated manner in order to make a more spectacular impression. In the shot where Campbell throws a roundhouse kick at the witch, Raimi added the sole of the protagonist’s shoe to one frame in post-production. The viewer barely notices this while watching, but our senses register and evaluate the perception with the appropriately enhanced effect.

It's Alive III: Island of the Alive (1987)

This endearingly twisted continuation of the insipid horror franchise sticks primarily to the paternal lineage. Cohen also remains faithful to the concept of very rarely showing the mutant killer babies and the results of their attacks, because he doesn’t have the resources to make them look good. Therefore, in the first instalment of the franchise, he relied on developing the absurd premise into a trashy parental drama and on drawing out the suspense before the confrontation between the father and his spawn. While this may seem surprising in the case of a series of movies about murderous mutant infants, it’s not until the third instalment that Cohen really sets out into the realm of understated WTF that becomes an attraction in and of itself. Here the narrative unfolds through unexpected peripeteias that surprise viewers with their randomness and the characters’ suddenly finding themselves in grotesquely warped situations. The fact that the film’s protagonist is an unlikable asshole who irritates those around him with moronic one-liners and by singing annoying hackneyed songs only adds another level of goofy unpredictability, as the characters can suddenly find themselves in Cuba or throwing up on someone in a car. Cohen took an utterly serious approach to trash, which gave his films a uniquely likable and appealing aura. It’s hard to say whether he let go of the reins here because the franchise was already in the toilet or because he knew he could actually get away with anything in the third instalment of this phantasmagoria. Maybe both, because Island of the Alive turned out be annoying and entertaining at the same time.

My Mom's a Werewolf (1989)

Typical hopeless trash by Pirro in combination with Fischa, another immigrant who, thanks to the insatiable video market with no requirements for quality, found a stable career in making questionable films. My Mom’s a Werewolf is mediocre, uninteresting drivel in which the most impressive thing is how long and vehemently the creative duo behind it can beat the dead horse of its premise. Only in the last quarter of an hour did they remembered that the film could actually be funny and thus switched to sitcom slapstick mode. However, that doesn’t make the whole thing some sort of comedy gem. But after all of the insipidness, the climax is actually entertaining, which simply no one would have expected. After getting taken at the video rental shop and taking this exercise in futility home, the viewer would actually be glad that it wasn’t entirely a complete waste of time. Especially with the help of the magical fast-forward button, whose use the filmmakers themselves may have counted on.

Jackie Brown (1997)

Twenty-five years and six or seven films later, Jackie Brown remains Tarantino’s most disciplined film, which makes it all the more pleasantly surprising. It’s tempting to wonder what alternative path his filmography might have taken if it had been a bigger hit in its time. Perhaps Tarantino would have taken more inspiration from other artists, with less showing off. Of course, that isn’t possible, not only because we can’t change the past, but mainly because the given period and the very nature of Tarantino’s personality had a greater influence on the development of his career as we know it. The expansion of DVD distribution and the internet boom with the attendant activation of movie fans had a tremendous effect on the spectacular eclecticism of Tarantino’s later work. Besides the fact that, as an egocentric boor and arrogant film nerd, he could not overcome his need to out-nerd everyone else and vehemently carve out his own monument to the untouchable and universally beloved pop-auteur. With this in mind, we can see how, even in his most modest work, he simply has to push himself to the forefront and imprint his ego on the telling of a story that doesn’t especially lend itself to that at all. From the voice on the answering machine and the megalomaniacal closing credits featuring his own name, to generating trivia that actually only highlights the filmmaker’s supposed sophistication, to the problematic aspect of Tarantino childishly and nerdishly showing off that, thanks to the number of blaxploitation movies he has watched, he can write more gangsta talk than real gangstas actually use. At the same time, however, it’s impossible to deny Tarantino’s obvious talent as a filmmaker, his masterful understanding and use of the medium’s means of expression, and his brilliance in constructing fictional narratives that work extremely well even though they merely rely on other works of fiction and genres rather than on reality. What’s even more surprising about Jackie Brown is that it is partially about aging. Not on its social and personal levels, but primarily in terms of the aging of film and genre icons. But let’s also acknowledge that, as a project in which a thirty-something cast his beloved fifty-somethings, Jackie Brown can actually bring to mind Tomáš Magnusek, with whom Tarantino perhaps has more in common than we would like to admit, though definitely not in the area of filmmaking skill.